The Patient is Not a Document: Moving from LLMs to a World Model for Oncology (Part 2)

We tested our model with Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s (MSK) data while participating in the MSK iHub Challenge 2025 cohort program, and we’re releasing the model weights to the public

TL;DR: We validated our Standard Model on real-world oncology data from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) during the 2025 iHub Challenge Cohort program, proving that a specialized architecture designed to simulate biological dynamics S(t) delivers superior predictive performance on complex, non-linear clinical tasks—and we’re making those model weights available today.

In Part 1, we introduced our Standard Model v1, our biological world model built on top of the Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture (JEPA). The core hypothesis of this design is that by training on cause-and-effect pairs (State at time t + Intervention → State t+1), the model learns a high-fidelity patient state embedding that captures the underlying biological dynamics of the disease.

However, model validation presents a nuance. Logic suggests we should ask the model to generate the “future trajectory” (e.g. predicted text or synthesize a follow-up CT scan) and judge the output. But our Standard Model projects the patient journey in the latent space, not in the pixel space. Therefore, evaluating based on raw signal generation is a category mismatch.

Instead of judging raw signal generation, our Standard Model tests the quality of the patient representation itself.

In a functioning World Model, S(t) is not just a summary of the past; it is a predictive vector that explicitly encodes the trajectory of the future. To verify this, we use a frozen encoder protocol: we freeze the model’s weights and attach a simple linear probe. Think of this linear probe as a “truth serum.” It is too mathematically simple to learn complex disease patterns on its own. For the probe to succeed, the prognosis must already be structured within the patient’s embedding.

The Proving Ground: The MSKCC Oncology Cohort

To stress-test a World Model, one needs more than just “labels”; one needs high-density longitudinal history. We utilized a massive, high-fidelity cohort from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) during the iHub Challenge comprising 23,319 patients and over 323,000 patient-years of data.

What makes this dataset unique for a JEPA-based architecture is its temporal density. With a median follow-up of over 50 months and an average of 127 clinical events per patient, the dataset provides a “high-resolution” movie of cancer progression rather than a grainy snapshot. The coverage is near-universal: 100% of patients have confirmed pathology and outcomes, and 95.6% have deep genomic biomarker data. This depth allows the Standard Model to move beyond simple text-matching and actually model the interaction between systemic therapies (94.8% coverage) and the biological state of the tumor.

Evaluation on MSK’s Cancer Dataset

Our evaluation pipeline is designed to prove that the model has internalized clinical logic rather than just memorized data.

The Workflow: From History to Embedding

Generate: We feed the de-identified patient’s longitudinal history up to a specific time point t into the model. Using our utility function, we convert raw clinical events into a chronological narrative (e.g., [2024-01-10]: Glucose: 110. [2024-01-12]: Dyspnea, etc.).

Embed: The model acts as a Frozen Backbone and outputs a single, fused patient state embedding S(t) to ensure we are testing the existing representation.

Probe: We train a simple, lightweight linear survival head (e.g., using CoxPH loss as learning objective) on top of this embedding to predict future outcomes.

The Methodology: “Point-in-Time” Construction

Oncology is not a static classification problem; it is a trajectory of shifting risk.

A patient’s prognosis changes dramatically between diagnosis, remission, and recurrence. To capture this, we moved beyond “one-patient-one-label” and adopted a point-in-time evaluation framework.

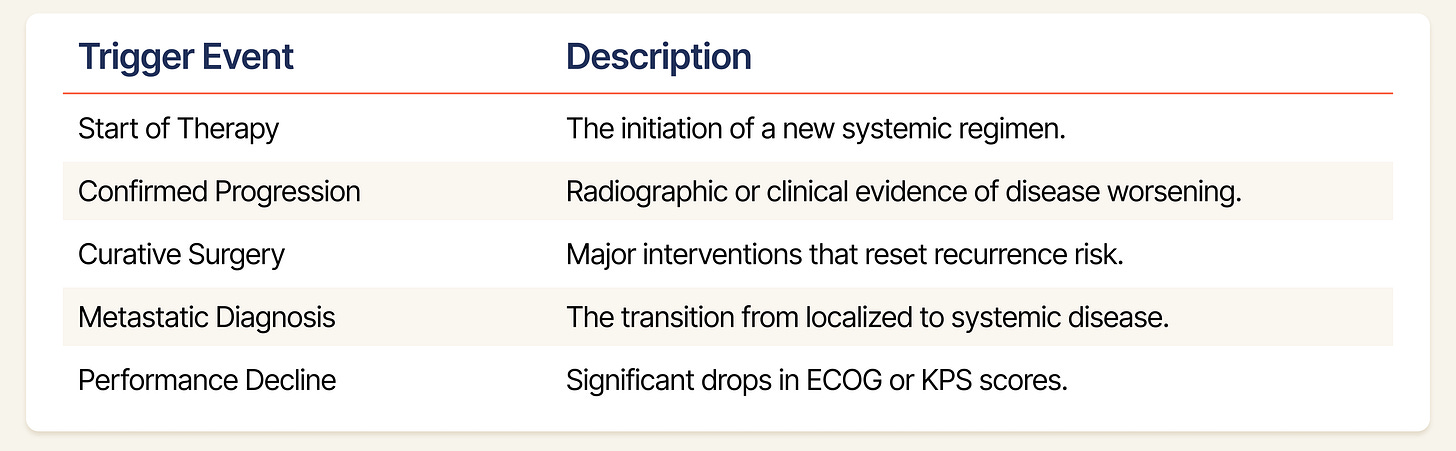

Selecting Indexing Dates (t=0): We slice a patient’s timeline into multiple examples based on clinically significant decision nodes. These are moments where the state of the patient undergoes a potential transition, and where a World Model’s predictive capability is most critical. At each indexing date, we mask all future data. The model must predict the trajectory solely based on the history available at t=0. Our generator scans the MSKCC patients’ event logs for five specific triggers to establish an indexing date:

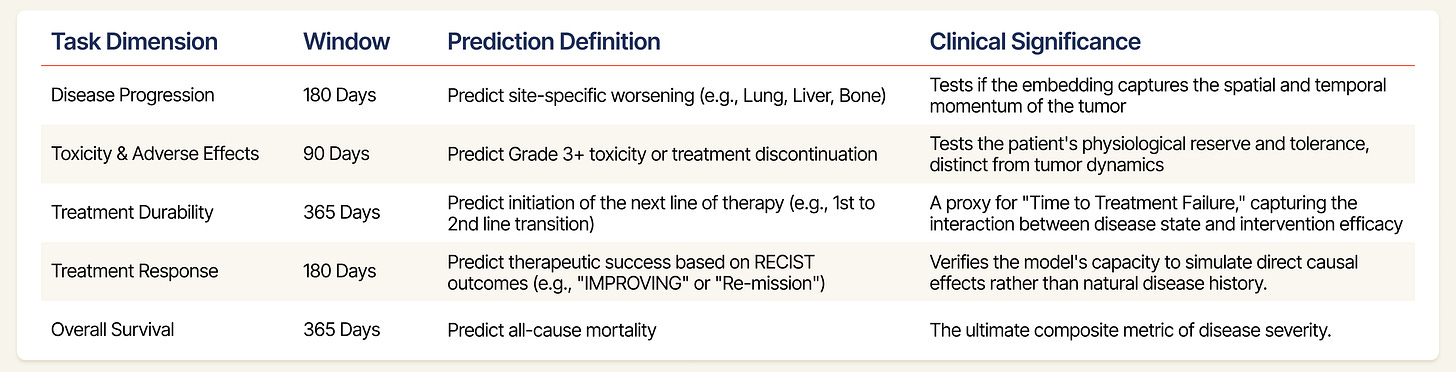

The Downstream Tasks (The “Future”): To ensure the embeddings S(t) are robust, we evaluate them against five distinct clinical dimensions as below using the linear probe:

Task Filtering: We don’t just test on every available label. To ensure statistical power, our framework only evaluates tasks that meet a high bar: a minimum of 500 total samples and at least 50 positive cases, ensuring the model isn’t just “guessing” on rare events.

Ensuring Scientific Rigor

Evaluating on Real-World Data (RWD) introduces risks of data leakage that do not exist in curated academic datasets. To ensure our results reflected genuine predictive power, we implemented strict guardrails:

The Patient-Level Split: A common pitfall in clinical AI is splitting data by records. If a patient has ten visits, and eight are in training while two are in testing, the model might “cheat” by recognizing that specific patient’s ID or baseline. We perform a strict Patient-Level Split. We shuffle the unique subject ID list and allocate 85% of patients for training and 15% for a completely “unseen” test set. If a patient is in the test set, the model has never seen a single day of their medical history during training.

Focusing on Progression: To ensure our predictions reflect true changes in health status, we remove data from the week immediately preceding a mortality. This prevents the system from basing its predictions on the administrative processes that occur during end-of-life care.

Strict Temporal Separation: To prevent intraday leakage (e.g., a toxicity event recorded at 4:00 PM influencing a prediction made at 9:00 AM on the same day), we enforce a 24-hour buffer. The target window explicitly begins the day after the Indexing Date.

Multi-Dimensional Metric Breakdowns: We don’t settle for a single AUROC number. Our framework automatically “slices” performance across two dimensions to find where the model excels or fails:

By Task: Comparing how it predicts mortality vs. line-of-therapy changes.

By Indication: Specifically analyzing high-heterogeneity diseases like Sarcoma vs. more “structured” cancers like Prostate.

Evidence

To test this, we benchmarked the Standard Model (SMB-v1-1.7B) against three distinct classes of baselines:

Classic Clinical Baselines: The industry standards - Logistic Regression, Random Forests, and Gradient Boosting.

General-Purpose Multimodal LLMs: Qwen3-VL (4B and 8B), to test if general-purpose AI models with massive scale can substitute for domain specialization.

Internal Controls (Ablations):

SMB-EHR-4B: Trained only on public EHR data.

SMB-v1-1.7B (sft): Trained without the JEPA objective (supervised fine-tuning only).

Here is what the data reveals.

1. A Structural Break in Clinical Reasoning

The most compelling evidence for the World Model hypothesis is found not in the aggregate scores, but in where the model wins.

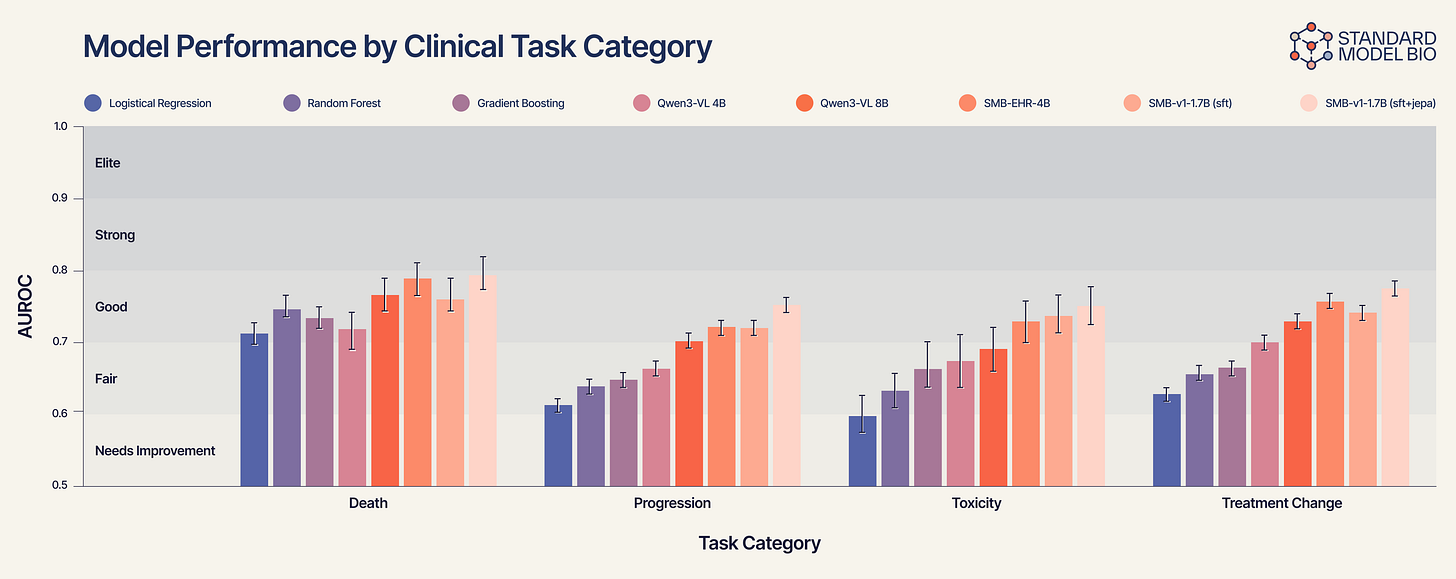

Figure 2 reveals a clear “staircase” of performance that correlates with biological complexity:

Static Tasks (e.g., Mortality): On simple outcomes like death, generalist models are competitive.

Dynamic Tasks (e.g., Treatment Change): As soon as the task requires understanding the vector of the disease, e.g., predicting disease progression or if a treatment will fail within a year, the generalist models collapse.

Gradient Boosting struggles at ~0.66.

Qwen3-VL improves slightly to ~0.70.

SMB-v1-1.7B (SFT+JEPA) dominates with an AUROC approaching 0.78.

This confirms our hypothesis. The SMB-v1 thrives here because it isn’t just looking at the patient’s current condition; it is simulating the treatment’s collision with the tumor’s trajectory.

2. Validating the “World Model” Architecture (SFT vs. JEPA)

To prove that our performance is a result of the architecture and not just the data, we ran an ablation study comparing pure supervised fine-tuning (SFT) against our hybrid architecture.

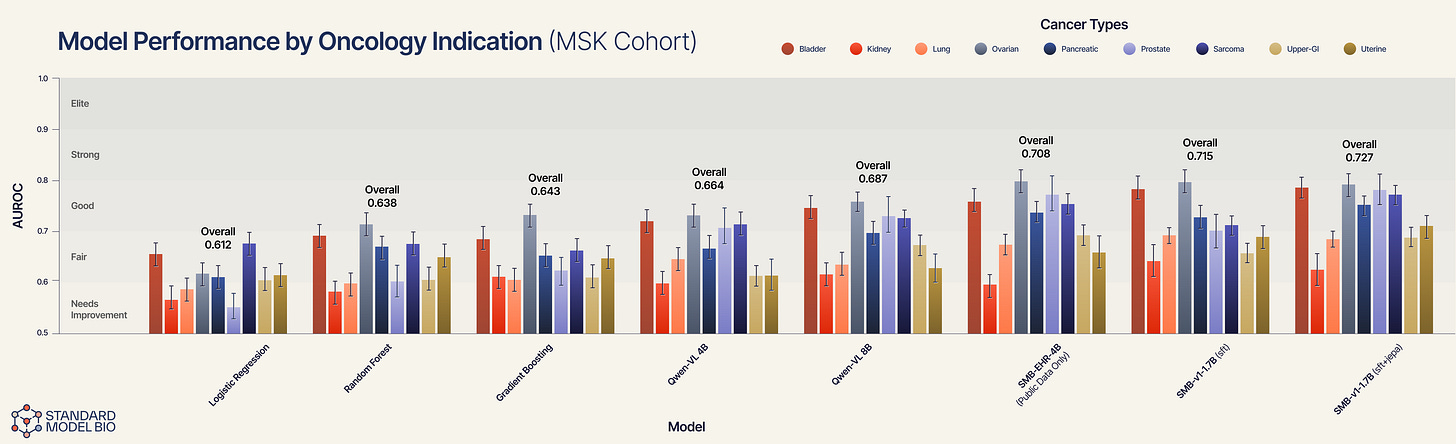

The Baseline (SFT Only): The SMB-v1-1.7B (sft) model achieves a strong overall AUROC of 0.715.

The Breakthrough (SFT + JEPA): When we add the JEPA objective that forces the model to predict future patient states, performance jumps to 0.727.

However, the aggregate score hides the true signal. As the error bars in Figure 3 reveal, the lift is not uniform. It is specific to complexity.

In relatively homogenous indications where text patterns correlate strongly with outcomes (e.g., ovarian cancer), the SFT model is already near the ceiling. The JEPA architecture shines where traditional pattern-matching fails: in highly heterogeneous, aggressive diseases.

Sarcoma (the heterogeneity test): Sarcomas are notoriously diverse and difficult to subtype from text alone. Here, the SFT model struggles (~0.71), but the JEPA model delivers a massive lift to ~0.77. The fact that JEPA lifts performance here suggests the model is ignoring the messy syntax of the notes and successfully embedding the underlying phenotype. It is learning “sarcoma-ness” from the trajectory of vitals/labs/imaging, rather than the text label “sarcoma.”

Upper-GI & Prostate: We see similarly distinct gains in upper-GI and prostate cancers. In these indications, the disease trajectory is often non-linear. The SFT model creates a static risk score, but the JEPA model successfully simulates the vector of the disease, resulting in superior stratification.

3. Specialization Beats Scale (The “Generalist” Trap)

A common assumption is that massive general-purpose models will eventually render specialized models obsolete. Our results suggest otherwise: domain grounding matters more than parameter count.

The Generalist: Qwen3-VL 8B achieves an Overall AUROC of 0.687.

The Public Specialist: Interestingly, our SMB-EHR-4B, which trained only on public data, surpasses the generalist with an AUROC of 0.708.

Why this happens: Qwen3-VL sees a lab value of “Creatinine: 1.8” as a sequence of text tokens to predict. The Standard Model understands it as a biological signal of renal function that interacts with hydration and chemotherapy toxicity.

4. Deep Dive: Granularity Beyond the Aggregate

Aggregate AUROC scores can obscure clinical nuance. Does the model actually understand anatomy, or is it just guessing risk?

Aggregate AUROC scores can obscure clinical nuance. Does the model actually understand anatomy, or is it just guessing risk?

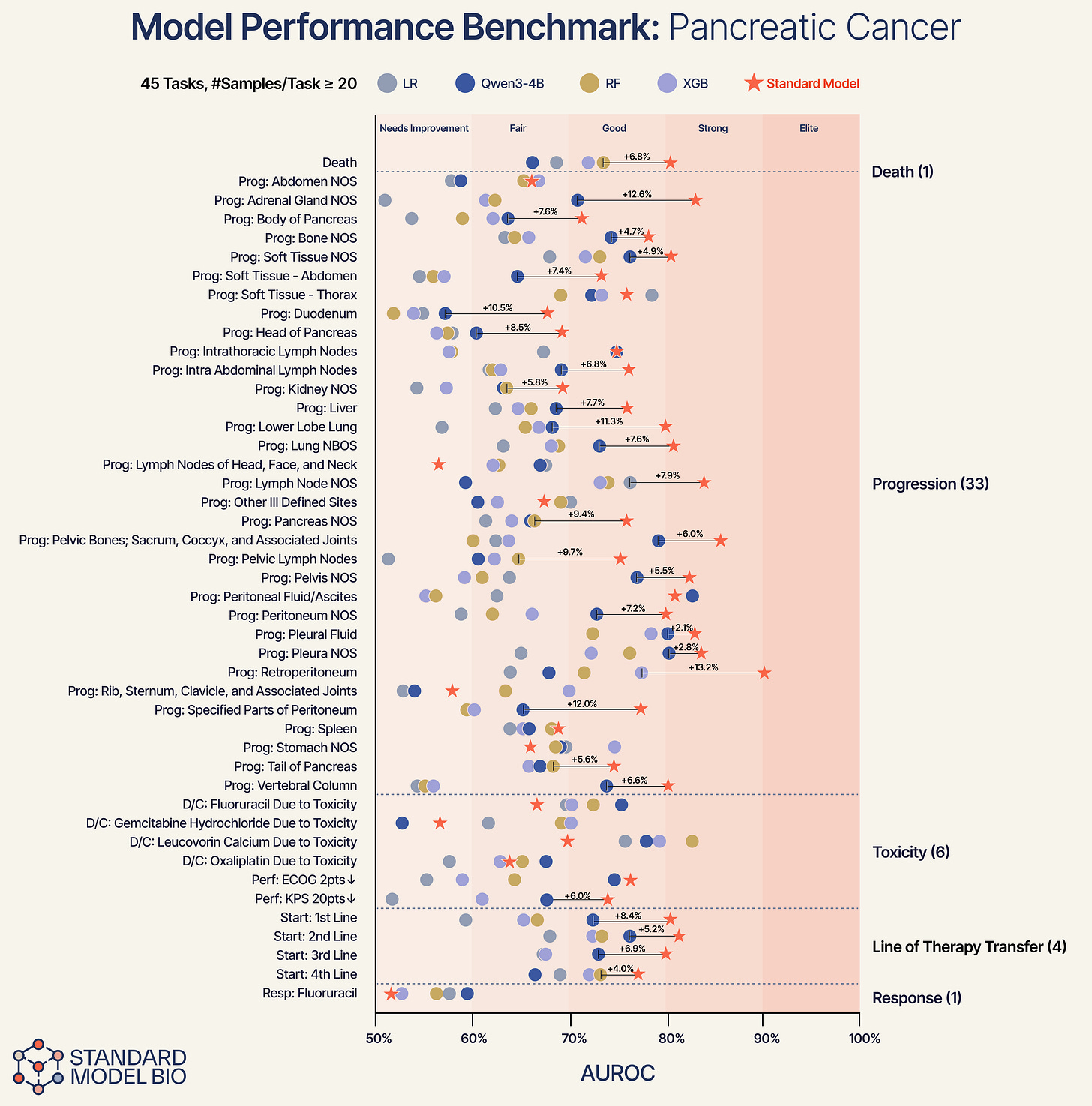

Using pancreas cancer as a representative demonstration, we broke down performance into specific anatomical tasks.

Anatomical Specificity: The model successfully differentiates between specific progression sites. For progression in the body of the pancreas, the Standard Model provides a +12.6% improvement over baselines. For progression in the liver, we see a +7.7% lift.

Consistent Superiority: Across 45 distinct tasks, ranging from high-noise predictions like “Discontinuation due to Toxicity” to “Line of Therapy Transfer”, the Standard Model consistently outperforms the baselines.

Conclusion

The hierarchy of performance is unambiguous: generalist models < specialized public models < specialized privately fine-tuned models < specialized World Models.

These results indicate that while domain-specific data provides a necessary baseline, the architectural approach determines the performance ceiling. The measurable lift of the JEPA objective over pure SFT confirms that enforcing causal structure in the latent space yields more robust patient representations than autoregressive text generation alone. Ultimately, achieving state-of-the-art clinical prediction requires modeling the dynamics of the disease, not just the syntax of the data.

Announcing the Availability of Our Model Weights

Standard Model offers a foundational step toward a broader vision: a reshaped oncology ecosystem where foundational models act as a partner in complex clinical decision making. By effectively modeling the patient state S(t) to simulate potential trajectories, we aim to support the entire care continuum - from refining early detection to guiding personalized treatment selection through what-if analysis.

In the longer term, this approach holds significant promise for accelerating clinical research. Specifically, the generation of universal patient embeddings enables synthetic control arms that could reduce reliance on large control groups, thereby decreasing trial duration and costs. Ultimately, our goal is to facilitate a systemic shift from “general approach” to precise healthcare.

That is why we are opening our model weights to the public. Visit Hugging Face here to access our weights and download them for use in your own workflow.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the MSK team that we worked with through the 2025 MSK iHub Challenge program, and especially the following for painstakingly contributing to dataset development.

John Philip, MS, Senior Director, Clinical & Translational Research Informatics and Data Strategy, MSK, New York, NY.

Neil J. Shah, MBBS, Assistant Attending Physician, MSK, New York, NY.

Nadia Bahadur, MS, Clinical & Translational Research Informatics, MSK, New York, NY.

Andrew Niederhausern, Bioinformatics Manager, Clinical & Translational Research Informatics, MSK, New York, NY.

Bryan Tran Van der Stegen, MBA, Business Analyst, Clinical & Translational Research Informatics, MSK, New York, NY.

Haiyu Zheng, MS, Business Analyst, Clinical & Translational Research Informatics, MSK, New York, NY.

Subscribe to our Substack to be notified when publish new posts, or follow us on LinkedIn, Twitter/X and Huggingface for more.