The Patient is Not a Document: Moving from LLMs to a World Model for Oncology (Part 1)

Standard Model: A new paradigm to build multimodal intelligence for oncology.

TL;DR: We built a multimodal foundation model for oncology that replaces the text-prediction of LLMs with the state-prediction of a World Model.

For the last three years, the game of biomedical AI has been simple: take a massive general-purpose model (e.g., GPT, Claude, Gemini), feed it medical text, and watch it crush the USMLE. It worked. We saw models passing licensing exams with expert-level scores and reasoning through complex vignettes.

But as the hype settles, the data reveals a sobering reality. When these same models are tested on realistic patient cases requiring actual treatment decisions, GPT-4 achieves just 30.3% completeness. Models struggle to measure tumor dimensions accurately through CT scans or to track disease progression without heavy reliance on external tools. In short, general-purpose AI models demonstrate exceptional retrieval capabilities on standardized exams, yet lack the grounded utility required for complex medical practice.

So, what did we miss?

Language Cannot Represent Biological Complexity on Its Own

The disconnect of general purpose AI for medical treatment lies in a single, flawed assumption: that language is a sufficient proxy for disease biology. The industry has assumed that if it built a high-fidelity map (the text), we would understand the territory (the patient).

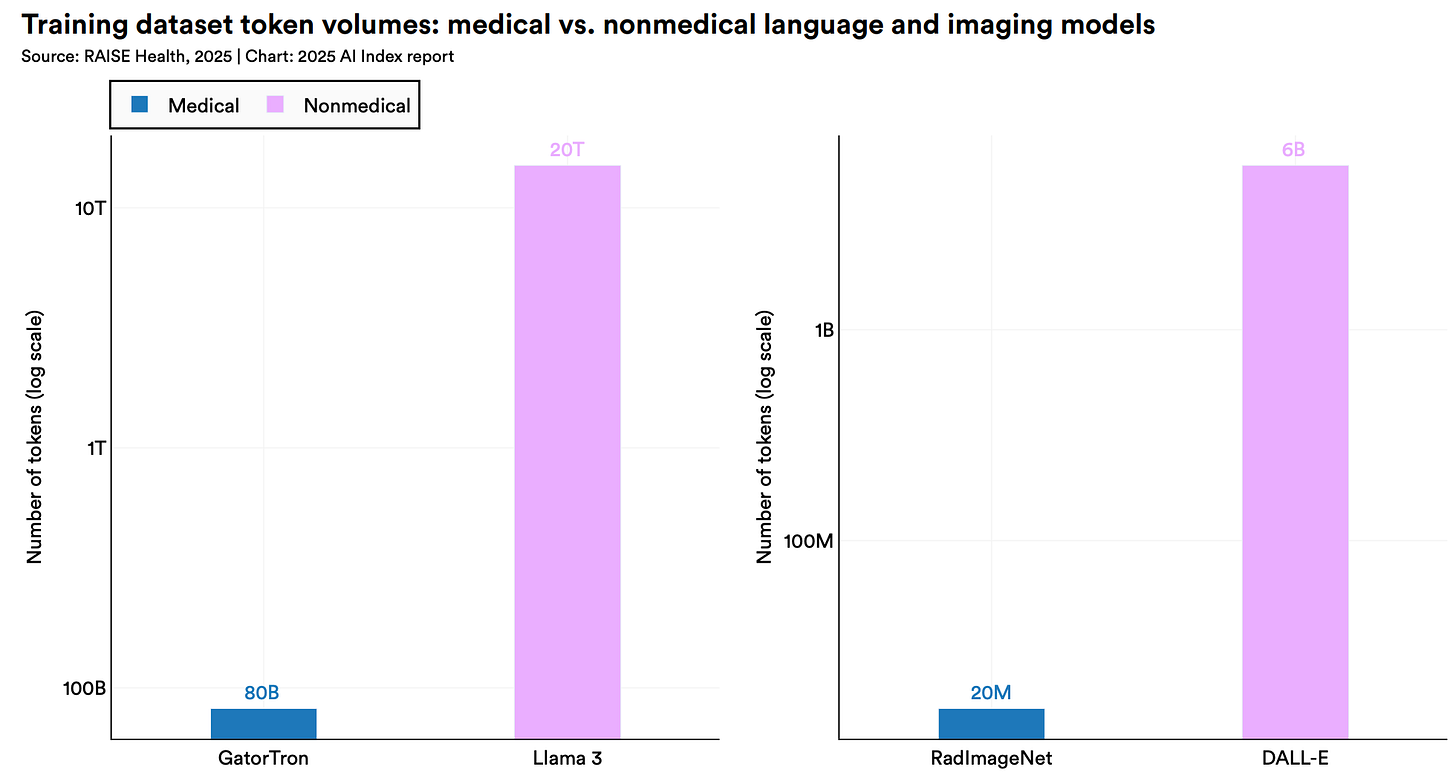

Today’s AI models were never natively trained on these foundational biological signals. The latest models from Google, OpenAI, and Anthropic have never “seen” an entire CT volume or “read” a whole-genome sequence; they have only processed text descriptions of them. And they certainly haven’t connected them to other signals across time and scale.

Human biology is not a linguistic problem; it is inherently multimodal. And yet, today’s AI is not. Biological signals exist at every scale, forming a complex, interacting hierarchy: from molecular variations in genomic sequences to cellular structures in histopathology slides, up to anatomical changes in CT volumes and longitudinal lab patterns in EHR data.

Even Specialized Models Hit a “Description Ceiling”

Moving beyond general AI models, the last 18 months have seen the rise of purpose-built foundational models in biomedicine specifically for oncology, known as the “savant” models. For example, Memorial Sloan Kettering’s Woollie detects cancer progression with a stunning 97% AUROC. Stanford’s MUSK predicts melanoma relapse with 83% accuracy.

These more specialized models are impressive, but they hit a ceiling because of two distinct challenges in the current landscape:

The “Text Bridge” Issue: Most systems today, like Woollie, function as LLM agents (or pure LLMs) that invoke external tools (e.g., segmentation models or mutation classifiers) and synthesize the results via text.

The Challenge: They treat cancer progression as a linguistic probability problem. For example, Woollie is trained on radiology impressions and summaries written by clinical professionals. It optimizes for semantic consistency with the doctor, not biological fidelity to the disease. By forcing biological reality through a text bottleneck, these methods suffer from lossy compression: they discard any biological signal the human observer failed to articulate (e.g., subtle textural changes in a raw CT volume). It cannot reason about biological signals that were never written down, e.g., a raw whole-genome sequence or the complex spatial topology of a tumor microenvironment.

The “Snapshot” Limitation: Current models hit a ceiling because they reconstruct static snapshots of a patient state rather than predict a journey through time.

The Challenge: Models like MUSK learn by reconstructing missing pixels in static CT images or aligning a histopathology slide to a static report. While they may output the probability of a future event (e.g., high risk of relapse) and identify that a tumor looks “dangerous,” they arrive at these conclusions by correlating static patterns, such as lymphocyte infiltration. These models effectively “skip” the causal chain of clinical events. Consequently, it is difficult for them to simulate how a tumor would dynamically evolve under Treatment A versus Treatment B because they optimize for pattern matching, not causal effect.

Focus Needs to Shift from Description to Dynamics

The fundamental problem isn’t that state-of-the-art LLMs need more medical text or that existing models need more data. The problem is the learning paradigm.

Clinical oncology is not a series of static snapshots; it is an evolving biological trajectory.

A clinician does not simply ask “Is this cancer?” (classification). Rather, they ask:

“Given the patient’s current state S(t) and this specific intervention I, what will their state be in 6 months S(t+1)?”.

We need an architecture that bridges the gap: one that possesses the semantic high-level reasoning of an LLM but is anchored in the multimodal “ground truth” of disease biology - genomics, proteomics, imaging, EHR and longitudinal outcomes.

Standard Model’s Approach: A Biological World Model

This is the motivation behind our Standard Model. By moving from autoregressive text generation and masked reconstruction to a Joint-Embedding Predictive Architecture (JEPA), we are ending the game of predicting words and beginning the complex work of modeling biological dynamics.

Architectural Deep Dive

Our Standard Model is a biological world model1 that operates as a temporal loop, transforming disparate clinical signals into a cohesive, evolving “digital twin.” The architecture is defined by four specific design heuristics:

1. The Inputs: Modality Ingestion & Fusion (Time = t)

Rather than relying on text as a lossy compression layer, Standard Model captures a 360-degree view of the patient. We ingest raw signals—such as genomics, proteomics, high-resolution imaging, and EHR data—and pass them through modality-specific encoders.

The Modality Fusion Heuristic: A specialized projector maps these raw encodings into an universal latent space of a state encoder. We don’t freeze the image encoders; we align the raw biological signals directly with the encoder’s strong world knowledge foundation. This yields a “fused” patient state embedding that retains both high-level semantic context and low-level biological granularity at time t.

2. The Engine: The “What-If” Simulation

This is the core differentiator. Once the fused patient state embedding is generated, the model does not simply output a diagnosis. Instead, it functions as a state predictor.

Input: Current Fused Embedding S(t) + Intervention A(t).

Output: Predicted Next-Time-Point Embedding S(t+1).

Cause-and-Effect Data Structuring: To enforce causal learning, the training data is not fed as a static batch. It is structured in a strict cause-and-effect format: (Pre-State + Intervention) → (Post-State). By explicitly modeling a given Intervention as the catalyst for state change, the model learns to distinguish between the natural history of the disease and the specific impact of a treatment.

The Shift: We do not ask the model to generate the pixels of the next CT scan or the text of the next report. We ask it to predict the future state representation in the latent space. This forces the model to learn the causal trajectory of the disease rather than the texture of the data.

3. The Anchor: Hybrid Optimization

Pure JEPA models often suffer from “training collapse” (outputting constant representations) or drift. To prevent this and ensure clinical grounding, we employ a hybrid learning objective.

The Strategy: We combine supervised fine-tuning (SFT) with JEPA objectives by assigning mixed weights to these learning signals.

The Result: The SFT component anchors the model to ground-truth clinical outcomes (e.g., “Did the patient respond to drug A?”), while the JEPA component forces the model to learn the underlying dynamics of how that state was reached.

4. The Optimization Loop (Time = t+1)

We trained our StandardModel-v1 (available on Hugging Face soon) on real-world longitudinal oncology data. The model compares its predicted future state against the actual patient state (derived from the ground truth follow-up data). The error signal updates the model, teaching it the causal laws of how tumors progress and respond to therapy.

Conclusion: Modeling State, Not Tokens

For decades, we treated medical AI as a library problem; reading more, summarizing better, passing exams. But patients are not textbooks. They are dynamic, evolving biological systems.

Our Standard Model represents a shift from Reading to Reasoning, and from Description to Dynamics.

Next: Evaluation

Though we argued that oncology AI needs to move from describing a snapshot to projecting a journey. But how do you validate a projection? If we simply let the model generate text, we fall back into the trap of measuring syntax, not biology.

Instead, we test the quality of the state that the model learned. If our Standard Model is truly simulating the patient’s future (the territory), then the representation of that patient at any given moment S(t) should contain the “future” within it.

In Part 2, we will move from architecture to evidence. We will detail how we validated our Standard Model v1 on real-world longitudinal oncology datasets, defining “ground truth” not as static labels, but as dynamic time-windows for progression, toxicity, response, and survival. Subscribe to our Substack to be notified when we publish the second part of this series, or follow us on LinkedIn and Twitter/X for more.

In robotics and autonomous driving, researchers and engineers realized that predicting text or classifying images wasn’t enough to navigate reality. They developed World Models.

A World Model is not a knowledge base; it is a simulation engine. It learns an internal representation of how the environment works and, crucially, how actions change that environment.

A Classifier asks: “Is this a picture of a road?”

A World Model asks: “If I turn the wheel 10 degrees left at this speed, where will the car be in 3 seconds?”

This ability to simulate future states based on interventions is the “missing link” in oncology. A patient is not a static image; they are a dynamic environment. By treating the patient’s biology as the “world” and the treatment as the “steering wheel,” we can move from describing the cancer to simulating its trajectory.